This review contains discussion of sexual assault. If you have been affected by any of the issues that have been discussed or need assistance, please contact 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732), the national sexual assault, domestic and family violence counselling service.

“If I told you that I’d killed a man with a glance, would you want to hear the rest?”

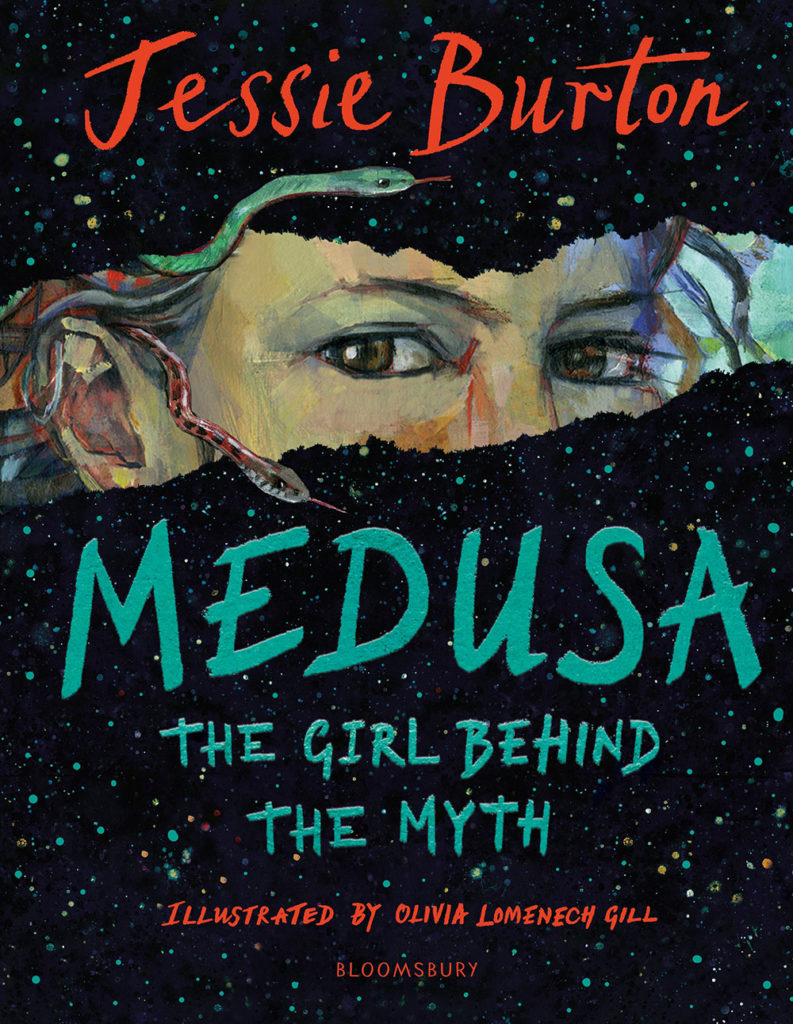

In the first line of Jessie Burton’s Medusa, here comes the conceit: despite being an iconic mythological figure, Medusa has historically been reduced to her snake hair and killer gaze. But every myth is a story, and the girl-turned-Gorgon deserves her own.

It’s worth noting that we’re going to be as spoiler-free as possible in this review. How could you spoil a millennia-old legend, you may ask? Let’s just say you could describe Burton’s iteration of the Medusa story as more of a reimagining than a retelling – key elements of the story have been modified.

The well-known version of Medusa’s story comes from two Greek texts – Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Hesiod’s Theogony. Ovid explains how Medusa turned into a snake-haired, killer-eyed Gorgon. She was a mortal with two immortal sisters living on the edge of Night. She ‘seduced’ Poseidon, who ‘ravaged’ her in Athena’s temple. Athena punished Medusa with the snake hair and eye situation – some say to avenge the temple, others say in jealousy of Medusa’s beauty.

Fast forward to Hesiod’s story of Medusa and Perseus. Perseus was sent on a quest by the king Polydectes to bring back Medusa’s head (there are reasons, but I’m not going to go into it – it has almost nothing to do with Medusa herself). Perseus is aided by Hades’ Cap of Invisibility, Hermes’ winged sandals, Athena’s reflective bronze shield, and Hephaestus’ sword. He sails to Medusa’s home during the night and, using the reflective shield to see without making eye contact with her, murders her in her sleep.

Burton’s Medusa begins with Perseus’ arrival. There are plenty of hints throughout that this is an alternate mythology. Perseus doesn’t wear Hermes’ sandals or Hades’ Cap of Invisibility. He doesn’t use Athena’s reflective shield to avoid making eye contact. But probably the most glaring difference between the old story and Burton’s is the one that gets the plot going: Perseus lands on Medusa’s island, thinking he’s completely lost, during the day.

Burton’s Medusa begins with Perseus’ arrival. There are plenty of hints throughout that this is an alternate mythology. Perseus doesn’t wear Hermes’ sandals or Hades’ Cap of Invisibility. He doesn’t use Athena’s reflective shield to avoid making eye contact. But probably the most glaring difference between the old story and Burton’s is the one that gets the plot going: Perseus lands on Medusa’s island, thinking he’s completely lost, during the day.

“‘Who are you?’ I called down. I spoke in panic, worried that Argentus’ suspicion of this new arrival would drive him to his boat at any moment. And I spoke in hope: it felt of utmost importance that this boy should stay on my island – for a day, a week, a month. Maybe longer.”

This one little detail gives room for a relationship. Medusa shares meals with Perseus, refusing to show her face (or hair). Talking together on either side of a cave wall, the two begin to fall in love.

Before I go on, I’d like to acknowledge that this book (and this review) contains descriptions of sexual violence. Reader discretion is advised.

Medusa shines in its dialogue; I can almost imagine it as a play. Through Medusa and Perseus’ conversations, Burton fills in the details of Medusa’s origin story, and draws poignant parallels between the classic villain and some classic Greek heroines – including Perseus’ mother, Danaë.

Though she doesn’t physically appear in the book, Danaë serves as the perfect foil for understanding why Medusa is a classic villain, and other mythological women with similar experiences are heroines. When Danaë is faced with an overbearing god (Zeus), she gives him what he wants, as quietly as possible. When Danaë is faced with an overbearing king, her demigod son gets in the way for her. And though Medusa explores the unfairness of which survivor gets to be ‘good’ or ‘bad’, it still pays Danaë the respect she deserves for the difficult decisions she had to make.

Medusa reflects, “I didn’t need to imagine how Danaë had felt. Her own space, the little patch of land beneath her feet that belonged to her, invaded inch by inch by a man.”

It’s important to draw distinctions between which parts of Medusa are reimaginings, and which are retellings. I’m not sure how I feel about this. I wonder if I’d be more content with a retelling without all the changes. I wonder if that would uphold the fill-in-the-blanks and the change-in-perspective about Medusa with more ‘credibility’, and banish away the argument I fear might arise that the two stories end differently not because Perseus shows up at a different time, but because of a fault in our universe’s Medusa.

But maybe Burton’s Medusa is just as credible, and I’m anticipating a reaction that will never come. Maybe, like Medusa, I need to let go of what others might think.

Burton isn’t satisfied with how Medusa’s origin story is written in textbooks. She can read between the lines, and she doesn’t want to have to. Here is the reality: Medusa was assaulted by a god, and then punished by another god for being the victim of said assault. The rewriting of this truth and the interrogation of the original story’s moral – that Medusa ‘brought it on herself’ – is a powerful tool in bringing the Medusa story into the modern day.

And, no, this part isn’t a reimagination.

“Poseidon didn’t care whose temple he was entering… He just pulled the pillars down. I screamed for him to leave me alone, I called out to Athena, I said, No, no, no! But in the rubble of that night, Poseidon took what I had never wanted to give him. Me.”

Burton’s style does a lot for the modernisation angle of Medusa. It’s first person, it’s casual, and it’s brutally honest. While it’s not always as crisp as it could have been, and occasionally a little too overt in its messaging, it’s an understandable choice by Burton with a theme like sexual violence on the table — it’s hard for an author to trust a reader to get the idea.

That said, Medusa is a heartwarming and heartbreaking story about a villain I never thought I would have so many feelings about. If it proves nothing else, it proves this: Greek myth reads a lot different when you look closely.

‘Medusa’ is available now via Bloomsbury Publishing.