Sydney

June 21-22, 2025

Sydney Showground Olympic Park

Godzilla – the name alone conjures images of Tokyo on fire; the giant beast letting out its iconic roar and flattening everything in sight. Right off the bat, Japan’s favourite kaiju has the most important asset of all: brand recognition.

For over six decades, the radiation-spewing monster has instilled itself in the public consciousness, both in the East and the West. After making the leap from Japan to America twice – once in 1998, and again in 2014 – why does the character persist in the minds of audiences on both sides of the cultural divide, and how can he survive in the age of the cinematic superhero?

The cast of ‘Godzilla II: King of the Monsters’, set for release May 30

While the lovable giant may superficially fit into a modern action-adventure blockbuster perfectly by providing plenty of opportunities for the prerequisite lashings of computer-generated mayhem, it also carries a great deal of cultural import. Created only a short time after Japan’s involvement in World War II ended with the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Godzilla is more than just a man in a rubber suit. He’s an anti-war symbol, and a warning against the abuse of technology.

Directed by Ishiro Honda and released in 1954 by Toho Inc., the original Godzilla still holds relevance in a society just as obsessed today with conflict and the march of progress. Godzilla is a story of guilt, and the creature itself is a manifestation of punishment for mankind’s actions. And like many superhero tales, it’s also one of redemption and making amends for seemingly unforgivable sins. The parallels are too hard to ignore; with origins that echo those of Spider-Man, Godzilla gained his powers from accidental exposure to radiation. The similarities continue in that Spider-Man is a story about great power and great responsibility, in the same way that nuclear power and the responsibilities that come with its misuse are major themes of Honda’s 1954 film.

But isn’t Godzilla the one destroying Tokyo time and time again? With so much death and destruction under his metaphorical belt, it’s easy to see why Godzilla has been so often misconstrued as a “bad guy”. A brief look at his Japanese filmography shows this isn’t the case, where he was treated more as a force of nature than a vindictive, vengeful entity. It wasn’t long until he became a genuine “superhero”, saving the world from greater threats, starting with Anguirus in Godzilla Raids Again (1955) and eventually facing up against Ghidorah, the three-headed dragon – a creature whom we’ll be acquainted, or reacquainted with, in this year’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Like Marvel and DC, the Godzilla franchise has an extensive stable of characters to use as building blocks in constructing a cinematic universe. Where 2014’s American reboot introduced the Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms (MUTOs) – its own original enemies for Godzilla to battle – King of the Monsters is bringing back classic creatures from the long-running Japanese series. At least three recognisable entities will be making an appearance, including Mothra, Rodan, and the aforementioned King Ghidorah.

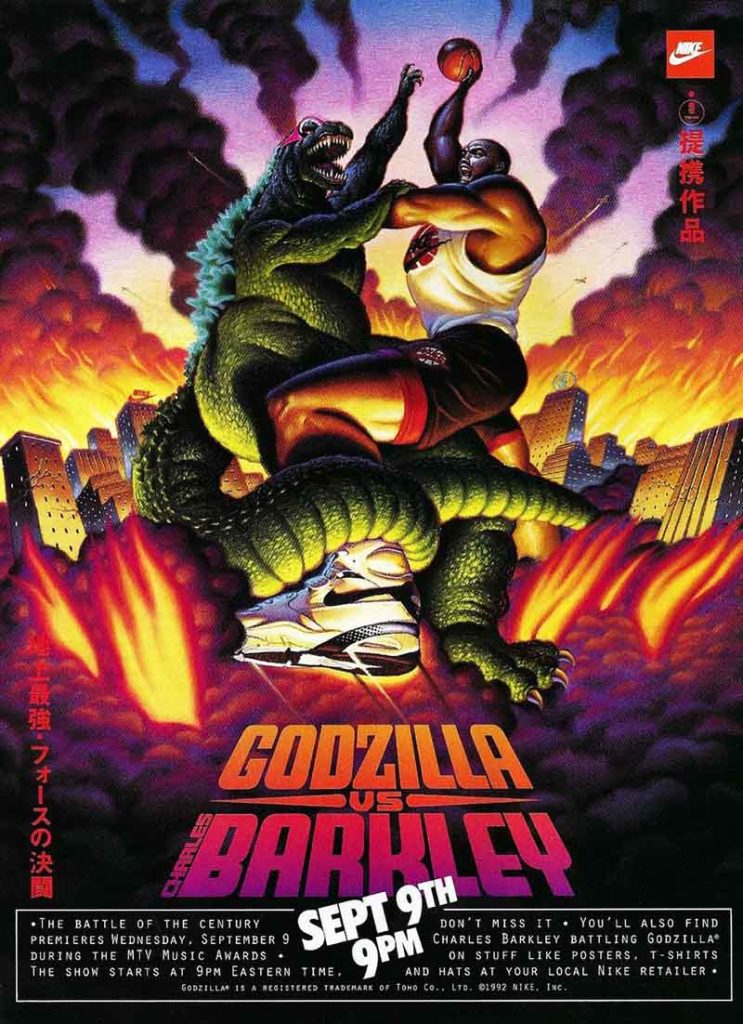

Godzilla’s cultural recognisability and marketability have never been in question. One big element of today’s cinematic universes is their potential for cross-promotion and branding to keep the studios in profit. While we’re not sure we’ll be seeing a line of Godzilla-branded cosmetics (à la Star Wars), there’s no doubt the license has the ability to shift countless toys, comics, video games and the like. Godzilla is a proven commercial entity, appearing historically on promotional materials as far-reaching as breakfast cereal, and even taking on Charles Barkley in a classic Nike advertisement.

Godzilla’s cultural recognisability and marketability have never been in question. One big element of today’s cinematic universes is their potential for cross-promotion and branding to keep the studios in profit. While we’re not sure we’ll be seeing a line of Godzilla-branded cosmetics (à la Star Wars), there’s no doubt the license has the ability to shift countless toys, comics, video games and the like. Godzilla is a proven commercial entity, appearing historically on promotional materials as far-reaching as breakfast cereal, and even taking on Charles Barkley in a classic Nike advertisement.

While the franchise has a rich history, one hurdle that may be difficult to overcome is the appeal (or lack thereof) of its less recognizable protagonists. Where Marvel is able to churn out films centred on characters whose names may not have rung a bell with audiences previously and turn them into household names, the Godzilla side-roster may struggle. On the surface, it seems far harder to get audiences excited about a standalone Mothra film than it was to inspire millions to buy tickets to a film with socially relevant characters like Black Panther. It could also be tough simply because a giant CGI moth doesn’t have the charisma of someone like Jason Momoa, but that’s not to say that an impressive story can’t be told with Mothra as the central focus by Western filmmakers. It’s more that the screenwriters will need to be careful in anchoring potential solo projects around the characters whom audiences recognise first, and then smartly build the profile of the less famous ones.

And that seems to be exactly what they’re doing. Out of the four current MonsterVerse films – with three in the can, and Godzilla vs. Kong due for release next year – only one doesn’t focus on Godzilla. Of course, the exception is Kong: Skull Island, and Kong himself has arguably more brand recognition than Godzilla.

As an example, the DC Universe stumbled by trying to bring together too many characters in too short a period of time. In trying to catch up with Marvel, DC jumped from Man of Steel right into Batman vs. Superman, where some fans were frustrated by the relatively hasty introductions of Wonder Woman, Aquaman, The Flash, and Cyborg. While that film received some criticism for the way it handled its characters, DC fared far better with its solo films. Both Wonder Woman and Aquaman were praised for taking their time to build their subjects in the same way that Marvel built Iron Man, Thor and Captain America before rushing into The Avengers.

Godzilla, as a franchise, holds enough appeal to ensure its resonance. Godzilla: King of the Monsters, which releases in Australia on May 30, looks every bit the event spectacle it needs to be in the current climate of action blockbusters. With the right screenplays, and supporting cast of likable human fodder, the MonsterVerse will have no trouble warming audiences to its kaiju – or as they’re now known, Titans.